Networking

The networking layer is a significant part of any blockchain and helps support all the features that make that protocol unique. Specifically, the networking layer dictates how nodes interact with one another — what transport layers they can use to communicate, how they gossip messages to all the other peers, and how they request/respond to specific messages from other peers.

When building any decentralized peer-to-peer (P2P) system, it must address Network Address Translation (NAT). Most of our machines, laptops, tablets, and phones are behind routers and firewalls, making it difficult for peers to establish direct connections. This is where the networking layer comes in.

While some other networking layers require the user to set up port-forwarding for their router to address the NAT problem, we designed our implementation with a focus on accessibility, using a combination of WebRTC and WebSockets for our transport layer. They use a plethora of techniques to help nodes establish direct communication. In other words, the Bitcoin Inu node implementation works right out of the box, either in a CLI environment or even directly within the browser. This makes it easy for anyone to use Bitcoin Inu, regardless of technical ability.

When a node is first launched, it needs to know of at least one other node it can connect to (known as a bootstrap node) that’ll introduce it to more peers in the network. That initial connection to a bootstrap node happens over a WebSocket, and all subsequent peer connections use WebRTC. This section will describe exactly how nodes connect to one another forming a network to support the Bitcoin Inu protocol, starting with how a new node starts.

Startup Sequence

As a new node starts up, the following happens:

- The new node randomly selects one bootstrap node from a provided list, and opens a WebSocket connection to it. If a user has a specific node they want to connect to during this step, they can use the config file or the command line to specify their own preferred bootstrap node(s). The bootstrap node sends its identity to the new node.

- The bootstrap node broadcasts a peer list to the new node.

- Using that list, the new node decides which peers to connect to.

- The 3rd step is repeated with every new peer the node connects with, until the maximum amount of connections (up to 50) is made.

- In order to maximize the strength of our network and to prevent network fragmentation, the node will prioritize connecting to peers that relatively few of the known peers are currently connected to.

As an end user, all this happens without you having to do anything, or even be aware of it. When you start a node, from your end, all you’ll see is your node connecting to a bootstrap node, and then quickly to many others.

Peer Connections Lifecycle

While a node is online, it tries to maintain a full and complete knowledge of the state of its peers, and all peers connected to those peers (two layers deep), checking periodically for any changes. Nodes have no knowledge whatsoever of more distant peers.

With that in mind, let’s look at how nodes communicate with one another by passing messages.

Messaging

A message is an agreed-upon format for a piece of information to be shared between peers. There are several types of messages and ways for them to interact with the nodes, depending on the situation.

Message Types

The networking layer of Bitcoin Inu currently has four different internal message types:

- Identity: a message by which a peer can identify itself to another

- Signal: a message used to signal a real-time communication (RTC) session between two peers

- Peer List: a message containing the list of peers that this node is currently connected to

- Cannot Satisfy Request: an error message when a problem occurs

All messages on the Bitcoin Inu network are routed via one of the following four styles, depending on various factors.

- Gossip: These messages reach every node in the network. When a node receives a gossip message, it validates the message and forwards it to other connected nodes. This is used to propagate changes to the blockchain to all the nodes in the network. We’ll talk more about this in the next section.

- Fire and Forget: These messages are directed to a specific connected peer (it is not possible to send a message to a peer you are not connected to). No response or receipt confirmation is expected from the peer. This is useful when you don’t need to make sure that the data was correctly received.

- Direct RPC: Here, a message request is sent to a specific connected peer, and the system expects a response. A remote procedure call (RPC) stream is composed of two streams: one for the request and one for the response. This is used as a backing layer for Global RPC.

- Global RPC: These messages are not addressed to a specific peer. The network library will choose a peer to send the message to and retry (up to a specified limited amount) with another peer if it doesn't get a response, or if the response is invalid. The selection algorithm is randomized, and weighted to favor peers who are known to be more likely to respond to the registered type of message.

Let’s dive a little deeper into how the gossip protocol works.

Gossip Protocol

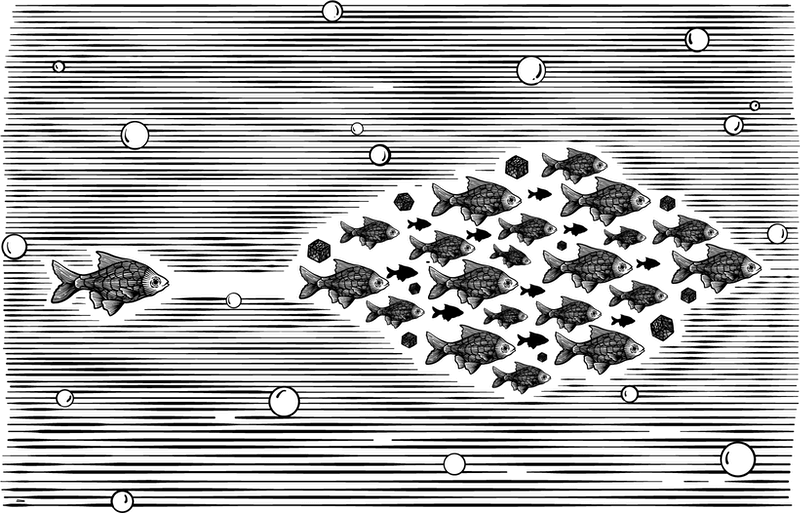

The Gossip Protocol is primarily used to broadcast new blocks and transactions to all of the peers within the Bitcoin Inu network. To help visualize this: nodes connected together form a network, and a blockchain is the data structure they agree on.

Back to the protocol. Once started, each node will then independently verify the incoming transactions before further broadcasting them out to other peers, and validate the incoming blocks before applying their encompassing transactions to the node’s local copy of the ledger (a.k.a. the blockchain). There is one main objective for the gossip protocol: when a message is broadcasted, every peer should receive the message as quickly as possible.

The following section details how Bitcoin Inu’s gossip based broadcast is currently implemented.

Basic Implementation

Step 1

When a new node comes online and connects with a peer, the peer communicates the list of their direct peers.

Let’s imagine that our current network is composed of a new Node A, connected to the nodes B and C. C itself is connected to nodes D and E. D itself is connected to F and G. Visually, this would look like the image below.

Visualization of how our example nodes are connected.

Nodes are only aware of their direct neighbors, and their neighbor’s neighbors. Node A will have no knowledge of Nodes beyond D and E.

Node A can now decide to connect to some of the peers, and will store a copy of each node peers list.

Step 2

When node A decides to broadcast a new message, it’ll send out a Gossip-type message to all of its connected peers (in this example, C and B).

Then, each subsequent node will broadcast the message to their other peers, until the entire network receives the message. In this example, C broadcasts the message to D and E. Then D broadcasts the message to F and G.

Optimization

To reduce network congestion, we implemented the following Gossip Protocol improvements.

Local history

In an effort to avoid an infinite broadcast of the same message, each node stores a set of all the gossiped messages it has seen. When a node receives a gossip-type message already in the set (meaning it was seen before), it ignores the message. The set that keeps track of these gossip-type messages is bound to a specific size and old ones are evicted in a first-in first-out order.

Neighbor cast

To avoid spamming the peers with duplicated messages, we implemented two other solutions:

- When Node A gossips a message to Node B, Node B does not send back the message to Node A.

- When Node A sends a message to Node B, Node B (knowing that A already took care of it) will avoid sending messages to any peer Nodes A and B are both connected to.

In the example below, Node A is connected to B, C, D, E, and stores a list of peers connections two levels deep.

When Node A gossips a message, the propagation happens in two steps:

- Node A broadcasts to Nodes B, C, D and E.

- Node B forwards the message to G. It does not forward it to C and E because it knows that Node A is connected to them and already sent it. Node C forwards the message to H. Node D forwards to I and Node E to F.

When Node F gossips a message, in this example, the propagation happens in four steps:

- Node F broadcasts the message to Node E.

- Node E forwards the message to both A and B.

- Node B forward to G. It does not forward to A because it knows that E is connected to A. It does not forward to C, because it knows it is connected to A.

- Node C and Node D both forward the message to H and I .

Looking Forward

We are exploring how to improve the block propagation at the application level before the main net launch. Instead of sending the entire block, a node will first send a header of the block. The peer node can then verify that it didn’t already receive it before requesting the data of the full block. We are also considering other implementations like IBLTs or Minisketch to understand the pros and cons of each solution.